Osborne in China: what will the UK do to get business there?

The exhibition by the great Chinese artist and dissident Ai Weiwei at the Royal Academy is remarkable on many fronts. It is dominated by the pressure and suffering to which the Chinese authorities have subjected him.

The half life-sized cells in sealed tanks, each with a little window through which you see Ai Weiwei’s crafted form in his cell with prison warders. He was incarcerated for 81 days without ever knowing if he would ever come out.

His extensive new studio complex on the outskirts of Shanghai was violently bulldozed by those self-same authorities. Ai Weiwei was by then present and captured the bulldozing on video, which plays on one of the walls of the exhibition. He rescued enough bricks to build a small tribute for this exhibition to bring what happened to him to a wider world.

There is a pile of crab-shells nearby – the remnants of a vast defiant party that Mr Ai staged as the authorities were doing their worst. He was then subjected to house arrest for the worst part of five years, and only now has a visa to come to Europe.

But you don’t have to look too far to find an example of the role of others in what gives the appearance of a degree of complicity with the Chinese authorities in censoring Ai Weiwei’s work inside his home country.

Phaidon is one of the biggest and most prestigious art book publishers in the world. Headquartered in the UK, it published the giant colour plate book The Art Book (2012), showcasing the work of a variety of great artists. Arranged in alphabetical order, Ai Weiwei is naturally to be found on an early page in most copies of the book.

But in the Chinese edition Ai Weiwei’s page has been removed. We have asked Phaidon how they can have been permitted this to happen. The Chinese company that publishes the Chinese edition is not a Phaidon subsidiary, instead the company has a contract with Phaidon.

Phaidon’s explanation is blunt: “Contracts are commercially sensitive and confidential, therefore I am sorry that we are unable to supply further details.”

The company will not discuss the matter further. In particular whether the contract permits the adulteration or censorship of the original work. Only adding as an after-thought: “Phaidon does not agree with censorship in any form.”

Providing a different version of material for a Chinese market is of course nothing new. In 1998, Rupert Murdoch reportedly instructed HarperCollins not to publish a book by Chris Patten – the last Hong Kong governor who was critical of the Chinese authorities.

The decision was taken at a time when Mr Murdoch was looking to expand in the country. And since then a variety of companies, large and small, have altered their editorial material to get business in China.

So the Phaidon Ai Weiwei matter resurfaces a big question. Individual companies aside, how supine are we as a nation prepared to be in bending our own rules and standards to accommodate trade with what may now be the world’s largest economy? Is that also why the British ambassador to China was one of very few western ambassadors never to visit Ai Weiwei whilst he was under house arrest?

Had the government been burned by the angry response to their meeting the Dalai Lama in 2012, which led the Chinese Foreign Ministry to warn of “serious consequences”? The possibility of those consequences may well spook companies – and countries – large and small.

In reality, though, Phaidon is a publishing house with a proud history of publishing high fibre and hard-hitting factual and journalistic books – including for example for many years the books of the photographic agency Magnum.

Many businesses and companies can claim they have to look past the politics of the companies they work in but for a publisher and especially a factual publisher there is a difference; they trade in the truth, or versions of it. Is its commercial enormity so urgently in need of selling in China that it is prepared to see censorship of one of its own products?

Not a bad question to ask with George Osborne drumming up trade for the country on this very day.

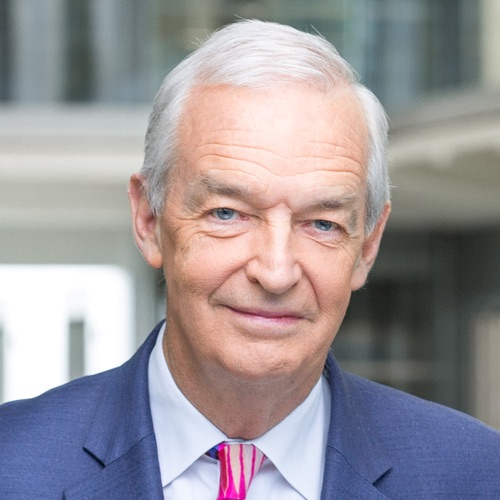

Follow @jonsnowC4 on Twitter