Gotcha boccia!

Jess Hunter, at 20, is by any test, severely disabled. She is also remarkably pretty. I’m not sure that it is even politically correct to say that. One day last month she ventured to our news studio in her cumbersome wheelchair with her “talent manager” and her assistant, and her coach. Jess is one of ParalympicsGB’s prospects for a gold medal in the upcoming Paralympic Games. Her sport is Boccia.

Her sport is what? Boccia rhymes with Gotcha and is, I reckon, the secret sensation of this month’s Paralympics. It’s just one of the remarkable sports that will take the games into another sphere from the breathtaking Olympics that have gone before. I suppose that its nearest able bodied relative is the French sport of boule, or our own village green game of bowls.

Her sport is what? Boccia rhymes with Gotcha and is, I reckon, the secret sensation of this month’s Paralympics. It’s just one of the remarkable sports that will take the games into another sphere from the breathtaking Olympics that have gone before. I suppose that its nearest able bodied relative is the French sport of boule, or our own village green game of bowls.

Jess Hunter was born severely affected by cerebral palsy. She has little or no control over any of her limbs and cannot speak. Her wheel chair tilts her in a 45-degree position half way between sitting up and lying down. Yet this extraordinary Para-athlete trains fifteen hours a week to sustain her position as one the world’s greatest exponents of Boccia. She is aided by an assistant who is not permitted to see the field of play – an area perhaps half a tennis court in size.

Jess is armed with six Boccia balls of varying weights. Using her eyes to signal which ball she wants to “throw”, Jess then has to line up the ramp from which the ball will be projected. The assistant moves it up, down, left, and right according to Jess’s eye signals. Once in position the jack is placed on a ledge on the ramp. There’s a groove at the back of the ramp and Jess – with huge difficulty locates it with a probe on her helmeted head. She locates the ball and prods with the probe. She repeats the exercise as she plays each of her six balls. Stunningly, her fist ball ends up nudging the jack. Playing in teams of two (Jess’s equally disabled teammate is 17-years-old), the field of play amazingly become a dense contest of tightly pitched balls. Suddenly one of the other contestants will blast the field open taking her own ball close to the newly positioned jack.

As the play unfolds, I, and my colleagues watching, all forget that we are engrossed in a contest between profoundly disabled young women, who cannot walk, or dress, or talk – playing a mesmerising and completely absorbing sport. For myself, with very little exposure to disability, my Paralympic journey as a commentator training for the games has been one of the most exciting and uplifting adventures of my reporting life.

I have played wheelchair basketball – one of the most savage sports I ever expect to play. I was crashed into, spun, tipped out, and constantly found the ball ripped from my grasp. Like wheel chair rugby it is an incredibly fast sport, skilled, making, like Boccia, for an extraordinary and all consuming spectator sport.

Blind cycling

As a cyclist though I have to confess that blind cycling is the sport that finally scared the lycra pants off me. A few months back I made my way to the Manchester velodrome to experience the sport. The track was swarming with Olympic and Paralympic cyclists alike. It was here that I encountered some of the British military amputees from the Iraq and Afghan wars. Some had lost a leg and sport incredibly engineered prosthetic that were cleated into the pedal. Others had lost an arm and were aided by brilliantly conceived handle bar grips attached to their artificial arms.

Blind cycling places you on the back of tandem with sighted rider at the front. I had never been on a tandem, never cycled completely blindfolded, and never ridden a fixed wheeled bicycle on which there are neither gears nor breaks. Oh, and I had never cycled in a velodrome.

Unsighted, the swoops up and down the sides of the track – the dives and spurts as you go faster and faster – were completely disorienting. I never knew where I was as I buried my head in the back of the rider in front. As we topped 43 mph I feared my ageing legs just would not be able to keep up. I screamed to be allowed to stop. But the exhilaration, the space, the wind, the crowd noise, and yes, once again the sheer sport obliterated my initial obsession with the disability.

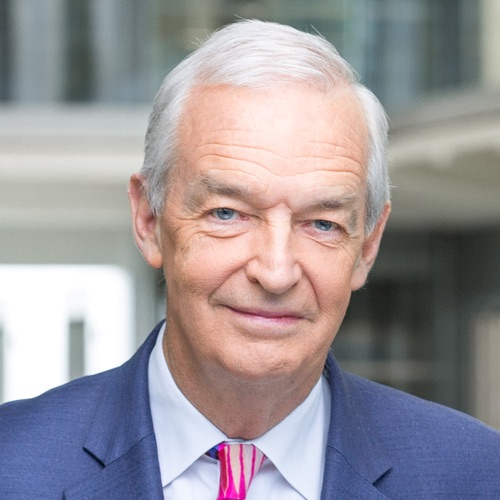

In Jon Snow’s Paralympic Show in the ten days leading up to the Paralympics, I’m going to share this adventure with you – meeting the Paralympians training amongst the rubble in Gaza; talking to the blind footballer whose brilliant left foot finds the ball by hearing the little bell that rings within it; and so much more. One of the most remarkable films in our half hourly nightly show will be an unprecedented access to the Military rehabilitation centre at Headley Court where many supreme Paralympic sportsmen have had their lives rebuilt and transformed. The Olympics may have thrilled us to the core; the Paralympics will take us somewhere else – one of the most exciting “places” I have ever been.

Follow @jonsnowC4 on Twitter.